What constitutes a good use of time, particularly for those who work independently? We want to do things ourselves, yet we also need to define healthy limits.

An Example

For example, we live in a world in which it has become remarkably possible to put together a website. Yet, is it a good use of our time?

This question comes up now because I have just taken time to revise my Beargrass Press website. Working with the Beargrass Press site, however, has taken me away from other concerns. It has also taken me back to an event last fall, when I was invited to participate on a panel with the objective of providing guidance to such professionals as scientists and lawyers interested in transitioning to work as independent editors.

I remain grateful to the conference organizers for the opportunity to reflect on my own path, time I would not have otherwise taken, as well for the chance to engage with others so dedicated to words. Those of us on the panel worked together to include presentations as well as opportunities for questions. As part of our presentations, we each offered a few suggestions that we hoped would be of use to those attending the session.

A Suggestion

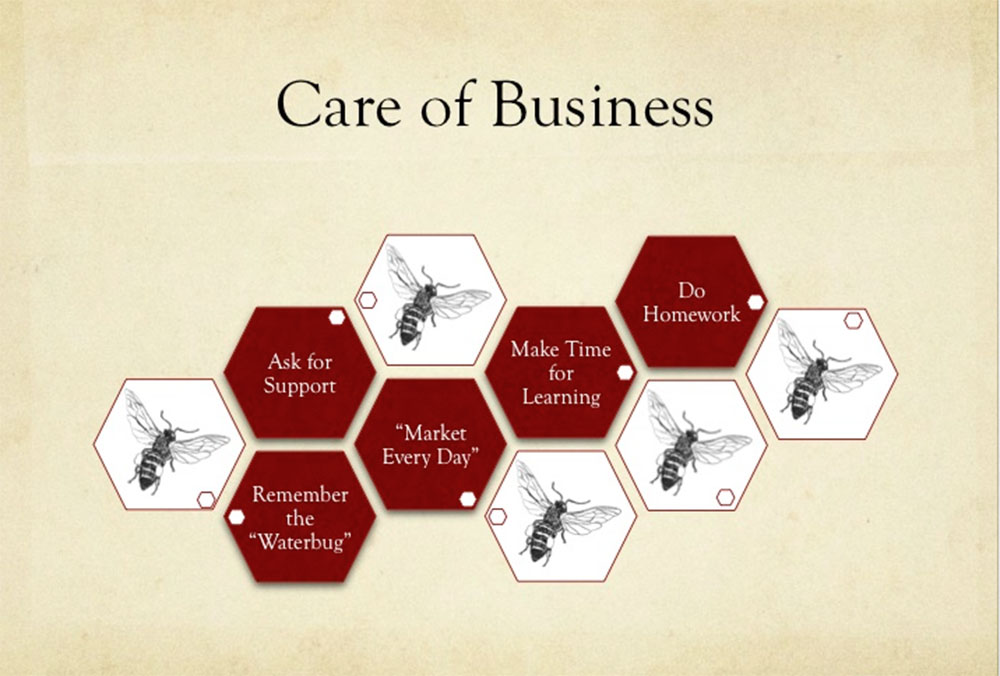

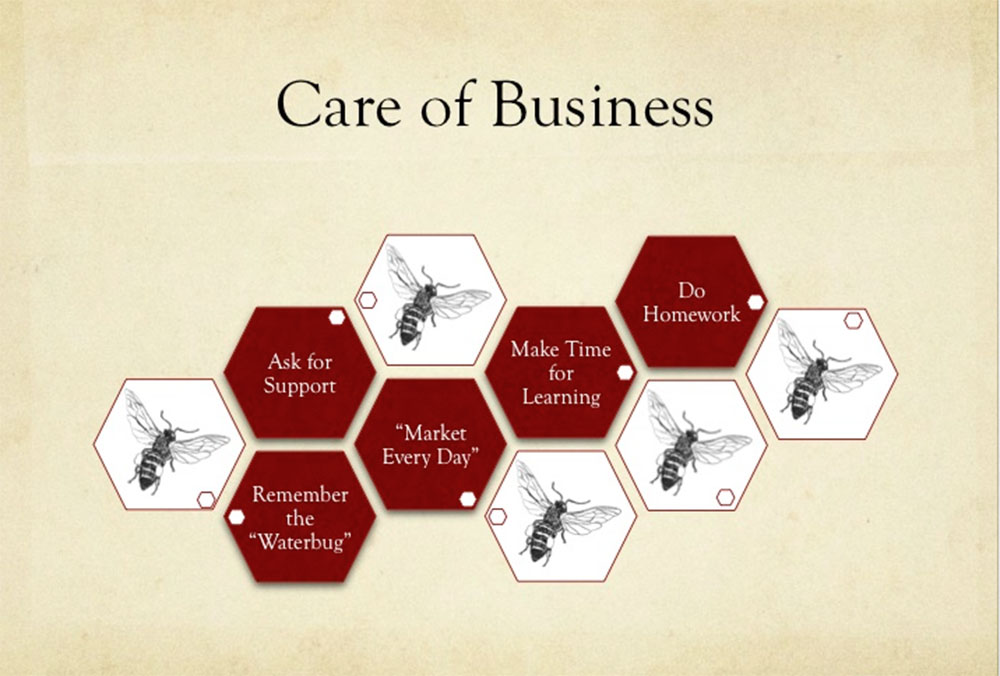

One of my suggestions involved being mindful of the approach we take to care of business. This is perhaps an obvious concern, yet I myself had no training in business, and many of my colleagues have similar backgrounds. As we know, being in business requires all manner of forms codes processes planning . . . seemingly countless, potentially overwhelming sets of to-dos. How is it that we might approach these many tasks? I added that it may be helpful to keep in mind to:

- Ask for support

- Do homework

- Make time for learning

- “Market every day”

- Remember the “waterbug”

These aspects of care, generally self-evident, are part of my toolkit. I have not come even close to incorporating the fourth item, the mantra of trusted individuals who have given of their time and energy in guiding me along my own path. The last is relatively new to me and may need some explanation.

Those of us attending the conference (Northwest Independent Editors Guild), as others committed to similar independent ventures that represent a growing part of today’s economy, face different challenges than those who have more-traditional forms of employment. We work alone—apart from a company or an established business with such staples as employees, IT professionals, accounting departments, marketing departments . . . along with health care plans, vacation days, and sick leave.

The Waterbug

The “waterbug” derives from the work of Jackie B. Peterson at the Small Business Development Center in SE Portland, near where I live. She suggests that, just as insects such as the water strider work with the surface tension at the point at which each foot (insects do have feet, though they do not have toes!) makes contact with water to stay afloat, independents often benefit by engaging the expertise and services of others to cover essential areas, which then helps them remain afloat. Our work with others, for example, might involve someone who takes care of our books, designs a marketing piece, or perhaps develops and manages a website, thereby freeing our time and energy to focus on what we are creating in terms of our business, what we want to to develop and grow and foster in the world.

A Better Example Next Time?

During the panel session, developing/managing a website was one of the areas I indicated a person might seek help with in order to focus on other issues, especially when getting started in business. I myself was advised to enlist such help when I decided I’d put off taking the website plunge long enough. I had to smile that day. On the heels of my presentation, one of the other panelists indicated that she had done her own website. I then heard the third panelist echo the same. I didn’t add that I, too, had done mine. It was clear that I would have done well to have chosen a different example for this group. The nature of our work is with words. In addition, independent editors tend to be, well . . . independent.

A Model with Merit

I nonetheless believe the “waterbug” is a model with merit. The issue concerns any of the multiple aspects of work that require our attention if we are to reach toward our goals. And the question remains: is what we are doing a good use of our time? How is it that we might maintain enough perspective in the course of all that needs to be done to find the means by which we might focus on that which is a good use of our time? I think it is a question worth asking, often. May we all do well in carving out our days in ways that work in wholeness with what we are creating in both our personal and our professional lives.

Recent Comments